By Rich McKay

ATLANTA (Reuters) – Holding signs and banners and chanting “Oil Kills,” protesters in Atlanta and other U.S. cities on Tuesday shouted support for Native American activists trying to stop construction of a North Dakota pipeline they say will desecrate sacred land and pollute water.

The protests against the Dakota Access pipeline have drawn international attention, sparking a renewal of Native American activism and prompting the U.S. government to block its construction on federal land, even as the company building the line expressed its commitment to the project on Tuesday.

“We were all moved by the spirit to be here,” said Linda James Thomas, 59, who attended the Atlanta rally in support of the Georgia State Tribe of the Cherokee.

When fully connected to existing lines, the 1,100-mile (1,770 km), $3.7 billion pipeline would be the first to carry crude oil from the Bakken shale directly to the U.S. Gulf.

Protests were scheduled throughout the day in Atlanta, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles and numerous other cities. Previous demonstrations have drawn celebrities including actresses Shailene Woodley and Susan Sarandon, and on Tuesday U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, a former Democratic U.S. presidential candidate, spoke at a rally in the nation’s capital.

“We cannot allow our drinking water to be poisoned so that a handful of fossil fuel companies can make even more in profits,” Sanders, flanked by activists in tribal dress and business suits, told the cheering crowd in Washington, D.C.

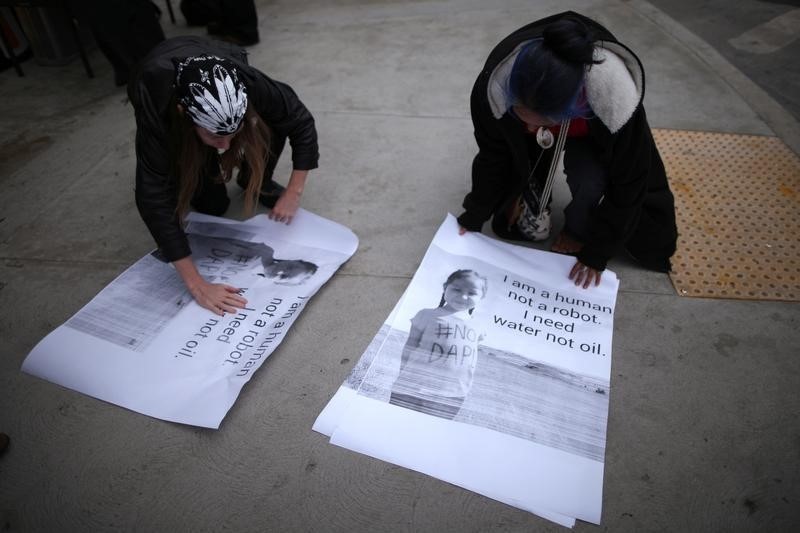

Protesters demonstrate against the Energy Transfer Partners’ Dakota Access oil pipeline near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, in Los Angeles, California, September 12, 2016. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

In Ohio, about 100 people gathered at a Cleveland intersection, some clutching bunches of sage and beating drums.

Tracey Hill, 46, a Cleveland resident who is one-eighth Cherokee, said she went last week to protest at the site of the pipeline project in North Dakota. “People are sick of being run roughshod over by corporations,” Hill said.

Activists took to social media to dub Tuesday’s rallies a national “Day of Action” against the pipeline. Many used the hashtag #NoDAPL to show their opposition.

Outside the United States, activists said on social media they planned protests in countries including Britain, Spain, South Korea and New Zealand.

Last week, the Obama administration, responding to the issues raised by the Standing Rock Sioux, whose land runs about a half-mile south of the pipeline’s route, said it would temporarily halt construction on federal land. Acting moments after a federal judge denied the tribe’s request for a halt to construction, the administration asked the company building it to refrain from construction on private land as well.

On Tuesday, Dallas-based Energy Transfer Partners, whose Dakota Access subsidiary is building the pipeline, said in a letter to employees it was committed to the project.

The letter did not address the federal request for a temporary halt of construction. But company officials said they would meet with government administrators.

“We are committed to completing construction and safely operating the Dakota Access Pipeline within the confines of the law,” Kelcy Warren, Energy Transfer Partners’ chairman and chief executive officer, said in the letter.

He dismissed as “unfounded” worries that oil would contaminate water in the Missouri and Cannon Ball rivers, and said the pipeline would address safety concerns connected with vehicle transport of oil.

“We have designed the state-of-the-art Dakota Access pipeline as a safer and more efficient method of transporting crude oil than the alternatives being used today, namely rail and truck,” he said.

In 2013, a runaway oil train in Canada crashed, killing 47 people, and in June 2016 a train carrying crude oil derailed and burst into flames in Oregon.

In coming weeks, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will review its initial decision to permit the pipeline and decide whether it correctly followed federal environmental law in granting permits.

Later this fall, the federal government will meet with Native American leaders to decide whether to reform its process for building infrastructure projects that will affect tribal lands.

In North Dakota, protesters have vowed to remain until the project is halted.

(Additional reporting by Kim Palmer in Cleveland, Catherine Ngai in New York, Valerie Volcovici and Ruthy Munoz in Washington, and Olga Grigoryants in Los Angeles)

Protesters demonstrate against the Energy Transfer Partners' Dakota Access oil pipeline near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, in Los Angeles, California, September 12, 2016. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

Protesters demonstrate against the Energy Transfer Partners' Dakota Access oil pipeline near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, in Los Angeles, California, September 12, 2016. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson