By Samia Nakhoul and Laila Bassam

DAMASCUS (Reuters) – – Hussein al-Khalaf, aged 13, burst into tears as he sat in his classroom at the Ahmed Baheddine Rajab school near Damascus, recounting why he is learning to read and write for the first time in his life.

He was five years old when the Syrian conflict began in 2011, shattering his life and that of his family in the city of Albu Kamal, which soon became a bastion for Islamic State.

Khalaf is one of thousands of Syrian children in a UNICEF emergency education program for those born during the war and who haven’t been able to attend school. Their school runs two shifts a day to allow as many children as possible to catch up with other kids.

“My parents said I should be in grade 1 but I wanted to be in grade 5 so that other children here won’t ridicule me. They mock me because I’m in grade 1 but I don’t respond”, said Khalaf, who fled with his family to Sahnaya near Damascus last year.

“I haven’t been to school since I was born. Daesh wanted to take us to join them,” he said, using the Arabic acronym for Islamic State.

“My friends all left, we all got separated. I found a phone number for one of my friends and called him. He told me ‘your friend Majed died’,” said a tearful Khalaf.

“Majed used to play with us. We were all together and living happily before Daesh came in. I want nothing. I just want to see my friends again.”

VICTIMS

Besides the fear that Islamic State would indoctrinate their children or take them as fighters, many parents did not send their children away because they might still be exposed to heavy bombing by Syrian and Russian planes.

Most children at the Rajab school were from the war-torn areas of Raqqa, Aleppo, Deir al Zor, Idlib and Albu Kamal. They were all displaced during fierce fighting.

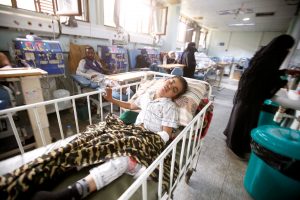

These children are among the principal victims of the war, now entering its eighth year. The trauma of what they have been through is visible on their faces, in their uneasy silences, sad eyes or tearful outbreaks.

They have paid a high price in a conflict beyond their understanding. Their lives have been broken with grief, their families displaced and dispersed, and they have been robbed of an education and a future.

In Syria, an estimated 7.5 million children are growing up knowing nothing but war, according to Save the Children, an international NGO.

WAR AND DESTRUCTION

“All that was there was war and destruction,” said Saleh al-Salehi, 12, who fled eastern Aleppo, a rebel bastion subjected to massive bombardment.

“My brother was killed. They dropped barrel bombs on us and fired rockets,” said Salehi, adding that it felt strange to be going to school for the first time in his life.

The school itself bears the scars of war. Classrooms are freezing cold and heating is a luxury, with fuel available only at sky-high prices.

The desks and benches are decrepit. Nothing of what is now common in modern schools, from laptops to digital activity centres, a library or cafeteria, was to be seen.

Even the headmaster was rushing out to a second job to make some more money to support his family. After 25 years, one teacher said her monthly salary was $80 and this had not increased in seven years.

Many kids look malnourished with black circles under their eyes, tattered clothes and torn shoes not warm enough to withstand the bitter cold.

Hussein al-Khalaf, 13, reacts as he sits in a classroom at a school in Sahnaya, near Damascus Syria February 1, 2018. Picture taken February 1, 2018. REUTERS/Omar Sanadiki

EMBARRASSED

While most said they were happy to have the opportunity to catch up with other children, they felt embarrassed and uneasy about their age and new environment.

Ali Abdel-Jabbar Badawi, 12, said: “I was dreaming about school. I haven’t been to school at all. A rocket fell on the school in our neighborhood and destroyed it. I want to catch up with the other kids of my age.”

Aya Ahmed, 13, from eastern Ghouta, a fought-over suburb of Damascus, said she was terrified of coming to school because she knew nobody and had no friends.

“In Ghouta I had friends but we couldn’t play. I didn’t know how to read and write.”

“I feel embarrassed when people ask me what grade I am. They look at me and say, all this height and you’re in grade 1. I was very late to get into school but I want to study and become an important person. I want to be a lawyer.”

The headmaster, Thaer Nasr al-Ali, said: “The conflict has affected all the people but the children paid a big price. They were deprived of education and were psychologically hurt. The schools were shut, they were cut off from education.”

“We had severe cases of trauma among the children because of the war and the violence they witnessed. Many kids lost parents and relatives and saw horror and death in front of their eyes.”

As well as losing out on education, many kids had to work to help their families or were recruited by militias and fighters, Ali and U.N. officials said.

CATCHING UP

UNICEF set up an emergency plan for accelerated learning in coordination with the education ministry so that students can catch up with other children.

The plan compresses one year into two and runs two shifts a day. There are 64 teachers for each shift and each class has 40-50 students. The school has 1,750 students, double the number before the war.

Syria had 20,000 schools before the war but only 11,000 are functioning; the rest are destroyed, semi–destroyed or being used by the armed forces or militia groups, UNICEF said.

In seven years of civil war, marked by sieges and starvation and the death of 400,000 people, half the 23 million population has been displaced or forced into exile. One third of the country has been internally displaced.

According to UNICEF there are 2.5 million Syrian refugee children living outside the country and 2.6 million internally displaced. The long term-impact on these children is huge.

“The drama of the Syrians is not finished. Even if the war ends tomorrow, the impact will be felt for generations,” said one relief official in Damascus, who declined to be named.

(Writing by Samia Nakhoul; editing by Giles Elgood)

![Rural women who have carried their malnourished children for days across the Sahel desert in search of [food] rush into an emergency feeding center in the town of Guidan Roumdji, southern Niger, July 1, 2005. [Niger's severe food crisis could have been prevented if the United Nations had a reserve fund to jump-start humanitarian aid while appeals for money were considered, a senior U.N. official said on July 19. Some 3.6 million people are in need of food, among them 800,000 malnourished children. About 150,000 may die unless food arrives quickly in the impoverished West African nation of 13 million.] Picture taken July 1, 2005. - PBEAHUNYKGE](https://d32l76m080vome.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2018/11/16120511/2018-11-16T175152Z_1_LYNXNPEEAF1GT_RTROPTP_3_NIGER.jpg)