By Dana Feldman and Hugh Gentry

LOS ANGELES/HONOLULU, Dec 7 (Reuters) – It has been 75 years, but U.S. Navy veteran James Leavelle can still recall watching with horror as Japanese warplanes rained bombs down on his fellow sailors in the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor that brought the United States into World War Two.

Bullets bounced off the steel deck of his own ship, the USS Whitney, anchored just outside Honolulu harbor, but a worse fate befell those aboard the USS Arizona, USS Oklahoma, USS Utah and others that capsized in an attack that killed 2,400 people.

“The way the Japanese planes were coming in, when they dropped bombs, they’d drop them and then circle back,” said Leavelle, a 21-year-old Navy Storekeeper Second Class at the time of the attack.

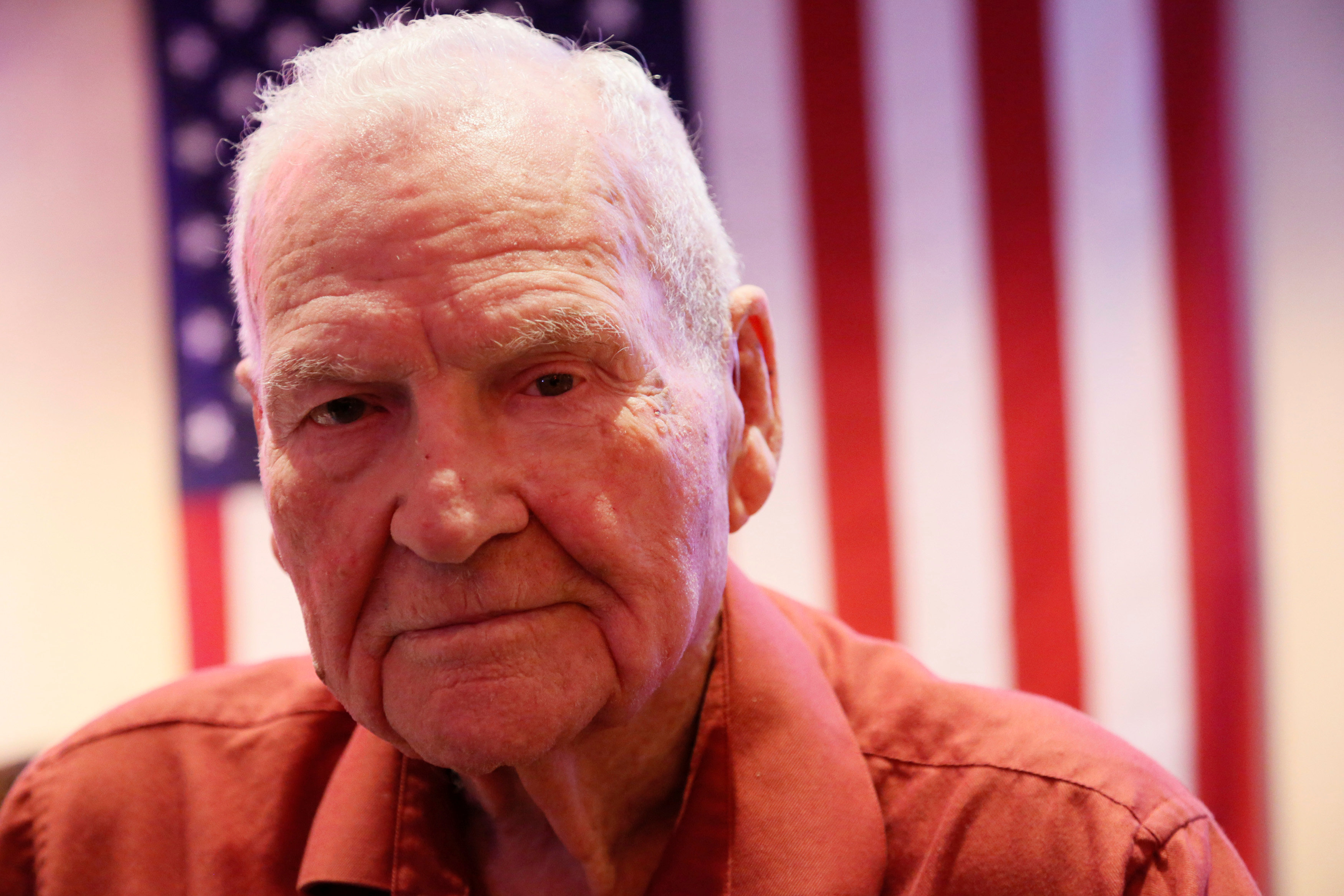

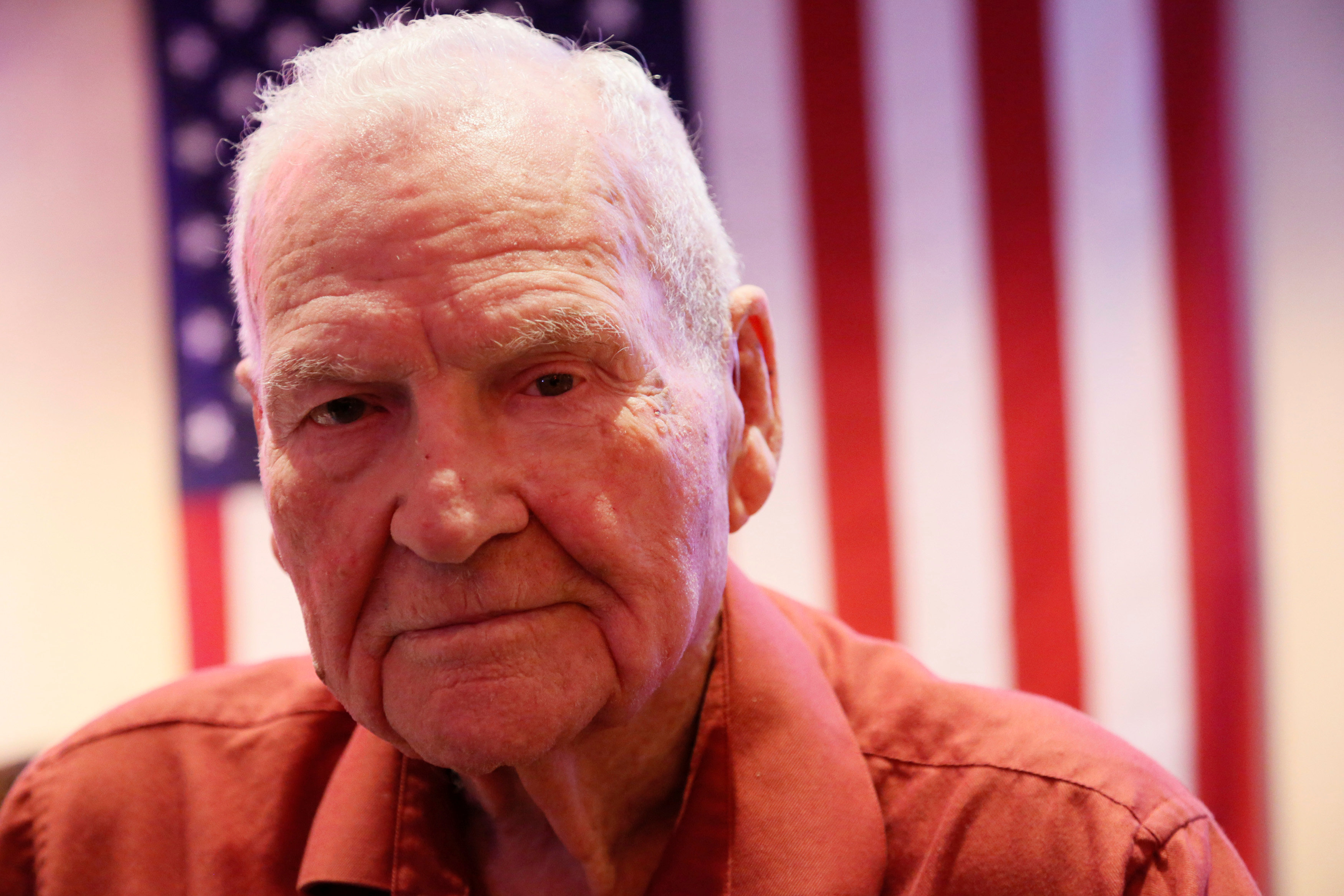

Leavelle, now 96, was among 30 Pearl Harbor survivors honored at a reception in Los Angeles before heading to Honolulu to mark Wednesday’s 75th anniversary of the attack.

James Leavelle, a 96-year-old Pearl Harbor Survivor, attends an event honoring 30 surviving World War II veterans who will travel to Hawaii to attend ceremonies for the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, in Beverly Hills, California, U.S., December 2, 2016. Picture taken December 2, 2016. REUTERS/Ted Soqui

The bombing of Pearl Harbor took place at 7:55 a.m. Honolulu time on Dec. 7, 1941, famously dubbed “a date which will live in infamy” by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt. Fewer than 200 survivors of the attacks there and on other military bases in Hawaii are still alive.

Wednesday’s commemoration at a pier overlooking the memorial to the sunken USS Arizona built in the harbor is set to begin with a moment of silence at precisely that time.

About 350 World War Two veterans and their families will be serenaded by the Navy’s Pacific Fleet Band with a musical remembrance made bittersweet by the knowledge that every member of the USS Arizona band – one of the best in the Navy – died that day.

Attendees will watch a parade, and two families will participate in a private ceremony in which the ashes of crew

members who survived the attack and later died, will be interred in a turret of the Arizona.

Across the United States on Wednesday, Americans will pause to remember those who died at Pearl Harbor, and the long and difficult war that followed.

WAR BEGINS

The shock of the Pearl Harbor attack is vividly illustrated in an exhibit at Massachusetts’ Museum of World War II, which features relics including a West Point cadet’s letter to his father – then-Brigadier General Dwight Eisenhower – on how to prepare himself for the coming war.

The United States declared war on Japan the next day. Three days after that, Germany’s Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States.

Pearl Harbor survivor Delton Walling walks with family members during a ceremony honoring the sailors of the USS Utah at the memorial on Ford Island at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii December 6, 2016. REUTERS/Hugh Gentry

Will Lehner, 95, was among those who had a chance to fight back in the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack. The 2nd class naval fireman was working in the boiler room at the USS Ward, patrolling the entrance to the harbor when crew members spotted a Japanese submarine.

“That submarine was on the surface and our skipper didn’t know if it was ours or not,” Lehner, 20 at the time of the attacks, said at the Los Angeles event. “He said: ‘Load your guns.'”

“The first shot went right over the top, the next shot right after it hit that submarine and punched a hole in it.”

After the war, a historical discrepancy nagged at Lehner. The remains of the Japanese submarine had not been recovered, and many historians doubted that it existed. That changed in 2002, when the sub was found.

“For 62 years,” Lehner said, “Nobody believed us.”

For his part, Leavelle would be touched twice by the hand of history. After the war, he became a policeman in Texas. On Nov. 24, 1963, he was the Dallas officer handcuffed to Lee Harvey Oswald when the accused assassin of President John F. Kennedy was shot to death by nightclub owner Jack Ruby.

(Reporting by Dana Feldman in Los Angeles and Hugh Gentry in Honolulu; Writing and additional reporting by Sharon Bernstein; Editing by Peter Cooney)